It is always somewhat dangerous to try to summarize a person’s legacy. Because it is a summary, it leaves out many aspects of a person, including some that are likely inconsistent with the overall portrait. We also tend to idealize those who have died.

And

yet, as we face today’s issues and challenges surrounding race and religion, we

do well to consider those who have gone before us who have faced similar

challenges, and evaluate how they responded.

Christians ask, “How would Jesus have responded?” Those who believe in active non-violence ask

how Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., or Mahatma Gandhi would have responded. Those who believe in more active

confrontation may ask how Malcolm X would have responded.

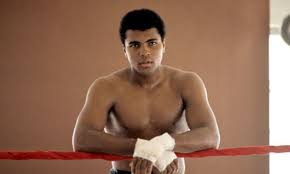

Before

embarking on this final post, a few words of summary of my journey thus

far. It began by reading several books

and articles about Muhammad Ali, and visiting his birthplace, museum and place

of burial in Louisville, Kentucky in June.

I realized

almost immediately that as a youth I totally misunderstood Muhammad Ali, seeing

him as a loud-mouthed braggart who did not represent the way I thought sport

should be played. However, I learned

that this was his way of gaining a national, and eventually international,

platform from which to speak. In

previous blogs I have talked about the way Islam transformed his life, his

political stance against war and violence, and the deep spirituality that

undergirded, strengthened, and directed his life. Now, Muhammad Ali’s legacy.

It is

hard to overestimate the extent of his influence, in part because he may have

been the most recognizable person in the world.

Famed sports reporter Dick Schaap wrote in 2001: “I’ve covered sports

for 50 years and there is no question that Ali is far and away the most

significant, the most charismatic, the most charming person that I’ve ever met

in sports. Nobody else is even in second

place. If the Queen of England, the

President of the United States, the Pope and Muhammad walked down Fifth Avenue,

a lot of people would say, ‘Who are those three people with Muhammad Ali?’ He was definitely the most recognizable human

being on earth and he probably still is.” [Muhammad Ali: Through the Eyes of

the World, 372.] African-American

sports sociologist Harry Edwards speaks to the kind of person Ali was: “I’ve been around great athletes all my

life, and I’ve long since gotten over being awed by them . . . . I wind up

dealing with their problems. I see their

human side, and it was from that perspective that I really came to appreciate

Ali. I don’t know of anyone who doesn’t

like Ali as a person. Even when he did

things that rankled, he carried himself in such a way that forgiveness was easy

because there wasn’t a malevolent bone in his body.” [Hauser, 450.]

Ali was

extremely generous, perhaps too much so.

He made a great deal of money over the years, and many people, including

many in his large entourage, took advantage of that generosity. But Ali had a massive heart, and he was moved

by anyone he saw suffering. Stories like

the following abound: He was at a dinner

honoring him at the Aladdin Hotel in Vegas.

He was awarded a large diamond ring.

Leaving the stage, he passed a little girl who was sitting in a

wheelchair. The mother asked Ali if he

would pose for a picture with her daughter.

He posed, hugged and kissed her, and then put the diamond ring in her

hand for her to keep. [Ibid., 368.]

His

generosity included not just giving away gifts.

One time in Los Angeles a Vietnam veteran was having flashbacks and was

on the 9th story of a building threatening to jump from his

balcony. Ali walked out to him, put his

arms around him, and brought him back.

He then spent $1800 on clothes for the vet and for an apartment in which he

could live.” [Ibid. 367-68.]

Ali also cared about other fighters. Ken Norton was only the second boxer to defeat Ali, breaking his jaw in Ali’s 43rd fight in 1973. Ali would win their next two bouts. In 1986 Norton was in a very bad car accident, which left him hospitalized for several months. Norton writes: “One thing I do remember is, after I was hurt, Ali was one of the first people to visit me . . . . I remember looking up and there was this crazy man standing by my bed. It was Ali, and he was doing magic tricks for me. He made a handkerchief disappear; he levitated. And I said to myself, if he does one more awful trick, I’m gonna get well just so I can kill him. But Ali was there, and his being there helped me.” [Ibid., 341.]

Another

story about Ali speaks to issues involved today in the Black Lives Matter

movement. Pat Patterson was a Chicago

policeman assigned to guard Ali in the mid 1970’s. He writes: “Being with [Ali] affected the

kind of policeman I turned out to be. I

was a relatively young man when I met him.

I was about 29, but I hadn’t been on the force long. And young police, they’re always interested

in locking people up. But with Ali, I

realized it was more important to be a peace officer, that people needed

help. He taught me to take time and

listen to people. Watching him, I

learned that power shouldn’t be used in a bullying way. The man was so caring; he cared so much about

people. And after a while, you had to know that the way he felt about people

was right.” [Ibid., 288-89.]

Actor

Dustin Hoffman summarizes Ali well, “They are right when they say fighting was

his profession, peace was his passion and grace is his essence.” [Through

the Eyes, 190.]

Because

of his concern for people, and his recognition throughout the world, at times

Ali served as an informal US ambassador.

In 1980 President Jimmy Carter sent him to Kenya regarding the boycott

of the Moscow Olympics. In 1990 he

traveled to Iraq to meet with Saddam Hussein.

After 10 days he was successful in having 15 hostages freed. One of them was Harry Brill-Edwards, who describes

his encounter with Ali: “I suppose what impressed me most about Ali was the way

he cared for everyone. He had a kind

word or gesture for absolutely everyone he saw.” Brill-Edwards then had the chance to fly home

on a State Department charter, but Ali was not invited on the charter, and

Brill-Edwards decided to wait to go on the same flight with Ali, explaining: “I

said to myself, I can’t do this. We should be in Muhammad Ali’s presence when

we go home. In the end, six of us stayed

on the flight with Ali. We did it out of

sheer gratitude and respect for the man . . . .I told my family when I got

home, ‘I’ve always known that Muhammad Ali was a super sportsman; but during

those hours that we were together, inside that enormous body, I saw an angel.’”

The

world has certainly not overlooked Ali’s legacy. He has received countless awards, including

the Arthur Ashe Courage Award, Sports

Illustrated’s Sportsman of the Century, the Presidential

Citizens Medal from President Bill Clinton, the Presidential

Medal of Freedom from President George W. Bush, and the Otto Hahn

Peace Medal in Gold of the UN Association of Germany (DGVN) in

Berlin for his work with the U.S. civil rights movement and the United Nations.

On November 19, 2005 the

$60 million non-profit Muhammad Ali Center opened in downtown Louisville. It

is a wonderful museum displaying not only boxing memorabilia, but it has as a

focus Six Core Principles of Confidence, Conviction, Dedication, Giving,

Respect, and Spirituality. Toward that

goal, the Center sponsors educational programs on such themes as Gender

Equality and Global Citizenship. On the

day I visited, as the Museum was closing for the day, a large group of young

folks were being welcomed in to the museum for a special program on global

citizenship. Throughout the Center 19

languages are represented, and the exhibit named the Hope and Dream Wall

includes over 5000 inspiring drawings and paintings created by children from

141 countries.

But perhaps for all of us blessed

to have children, the most important legacy may be left in the way they see us

and describe our lives. Hana Ali, writes: “In the last years of his life, my

father, Muhammad Ali, was as beautiful a man with a mission as he had ever

been. He glided across the ring of life

as though he were a Messenger of the Spirit.

No obstacle could bring his majesty down. His step, though slower in pace, was both a

testimony and a prayer that he lived in trust and not fear. No illness could take away his

brightness. It was ever-present in his

gleaming eyes and will carry on through the compassion and generosity that

flowed like a stream throughout his life.” [ESPN Magazine, 6/27/16, p. 95.]