The first task of philosophy is to teach us how to think clearly and rationally, including the development of critical thinking skills, so that we can sort through evidence and come to the truth, such as it exists.

What do I mean by “such as it exists?” In the ancient world, in both philosophy and theology, truth was thought to be absolute. Even the Enlightenment’s excitement over the idea that humans could be objectively rational and detached in their truth seeking held to the notion of absolute truth.

Modernism destroyed that notion. From Freud and Jung in psychology to Marx in economics to existential thinkers in philosophy to a host of theologians, including Albert Schweitzer, humans came to see the relativity of culture, history, and of almost all areas of knowledge. Many people became disillusioned, gave up the search for truth, and gave in to philosophies like Nihilism (there is no meaning or purpose in life, and no inherent morality) and Hedonism (the self-indulgent pursuit of pleasure, with ethics defined as seeking pleasure as the highest good and the aim of life).

As so often happens in life, the pendulum swings from one extreme (absolute moral principles) to the other extreme (no moral principles at all.) However, in spite of the general acceptance today that morality, culture, and theological truth is relative, within that relativity we need a concerted effort to find what is better, more true, more beautiful, more just, more humane.

An important way to approach this search for relative truth is by doing away with what in philosophy is called Consequentialism, commonly known in the expression that “the end justifies the means,” which asserts that if a goal is ethically important enough, any method of achieving it is acceptable.

Morality has to do with both content and process. By content I mean that one can and should take a moral position on any number of issues, from abortion to capital punishment to how we treat immigrants to when and if violence is ever appropriate (as the lesser of two evils). However, what I am talking about is process, which precedes content. Another term that can be used here is methodology. Philosophy challenges us to use a moral methodology as we move towards moral policy and positions. In order to have moral ends, we have to use a moral process.

Here is how Plato, who wrote extensively about the political order and the nature of the city, describes our task: (just as appropriate today as it was in the ancient world): “Plato stresses the fact that a man is most free within . . . society. He is most free when the correct structures have been set up around him by reason as a guiding principle, which will help him to become the most virtuous citizen that he can be. When every citizen within the city is virtuous, the city will flourish and prosper.” [Crawford, Plato, Rousseau, and the Implications of Moral Freedom, Illinois State University]

This is what is sadly lacking in so much political and cultural discourse today. As has been pointed out repeatedly, when the only goal is winning, then it is likely that little attention will be paid to the morality of the process. “Anything goes,” it seems, in politics today.

One of the results of this is a congress that gets little done, because there is a refusal to work together across the aisle as every conceivable parliamentary procedure is used to keep things form getting done as each party tries to achieve victory not with, but over, the other party.

At the same time we lack leadership from the executive branch because there is a clear lack of moral leadership there as well. Name-calling, bullying, and nastiness does not create the proper atmosphere for meaningful dialogue and significant policy decisions.

Adding to the problem is an evangelical wing of Christianity that overlooks racism, misogyny, and discrimination against immigrants as they seek the power to win the moral battles (content) most important to them. Whenever religious people embrace immoral tactics, they make hollow their call for moral stands.

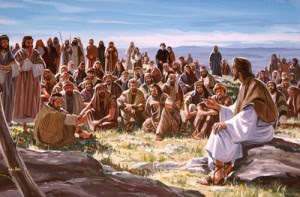

Spirituality is always concerned with process, insisting that it be moral. When we look at the teachings of Jesus, we see that so much of his instruction has to do with the moral process. He constantly challenges his followers to relate to others in a profoundly ethical way, demonstrating mercy, forgiveness, non-violence, generosity, hospitality and compassion. He ties these actions to what is in one's heart.

And he goes on to teach that only a good tree can bear good fruit. "Every good tree bears good fruit, but the bad tree bears bad fruit. A good tree cannot bear bad fruit, nor can a bad tree bear good fruit." [Matthew 7:17-18]

This is not an indictment of the left or the right or the center politically. The role philosophy has in politics is to guide all humans down a path that insists on using moral means and processes in the search for moral principles and stands. That, along with sound reasoning and critical thinking skills, will move us toward the society and political order we so desperately need as we confront the monumental challenges of our world today.

This applies not only at the larger, governmental arena, but to all of our human interactions at every level of society. From our families to schools to church to social organizations to Facebook and Twitter, we long for kind, considerate, respectful, and thoughtful discourse. And the only way that can be reclaimed is if each of us attempts to relate in moral ways to one another.

That is why we need philosophy again.