How My Theology Has Changed, Thank God

Part IX: Feminist Theology

So why and when would anyone take on such a daunting task? The main reason is that they have had a powerful experience that can no longer be understood and made sense of within the framework of one’s present theological understanding.

For me, this first happened as I lived through the experience of loss and grief following the deaths of both of my parents while in high school, and of my first wife, Pauline, after ten years of marriage. My first eight posts in this series essentially articulate the theological ways I searched to find meaning again, and a positive relationship with God, in response to my grief.

But there is another way in which our theology can change. It is not in response to our own painful experience, but to the painful experiences of others that is shared with us when we have an open mind and heart. Most of the remainder of my posts in this series will be of this type, and most of them fall into the category of what we call “liberation” theologies,” which search to free us from old ways that no longer work, if they ever did.

In general, traditional theology, which we often call Orthodoxy, begins “above” with traditional interpretations of theology and with the teachings of the church and then applies those understandings to our life in the world. Liberation theologies always begin “below,” in our lived experiences or as we learn of the lived experiences of others and then turn to the tradition for insight and guidance.

Liberation theologies give greater importance to our experiences. They are not automatically trumped by tradition. In fact, there may be times when experience challenges tradition, growing out of the “suspicion” that there are times when tradition not only does not reflect the will of God, but may be opposed to the will of God. Liberation theologies also tend to be more open to revelation, in the sense that God continues to speak to us. Our experience of God can be direct, and not automatically filtered through the lens of the tradition. This is, in fact, the deeper meaning of revelation: seeing something that no one has seen before.

This insight grows out of the theology of German theologian, Paul Tillich, and his teaching of what he called the “Protestant Principle.” Tillich begins with the dialectical nature of reality, comparing the unconditional to the conditional, the divine to the human, the infinite to the finite, the immortal to the mortal, faith to reason. Now, in traditional theology there is a strong emphasis on working to make sure that one does not profane the divine. Take the Ten Commandments for example. God’s name is holy, and we should not take it in vain. The sabbath day is holy, and we should not neglect nor misuse it. God’s truth is universal and absolute, and it should not be treated as if it were earthly and temporal and changeable.

However, what Tillich states in the Protestant Principle is that just as one should not profane the holy, one should also not elevate that which is finite and cultural to the realm of the sacred. This goes all the way back to the Protestant Reformation and theologians like Martin Luther, who rebelled against certain teachings of the popes of the time that they felt were not God’s eternal will. The one that bothered Luther the most was the pressure put on church members to pay money for indulgences, which were pieces of paper from the church that said your sins are forgiven. Luther also challenged the idea that priests, like himself, could not marry, and, after the Reformation, he did in fact get married and have children.

Feminist theology is one of those “liberationist” theologies,” beginning “below” in our actual experience in the world. It begins with us as humans, and includes our dreams and hopes, but also our pain and suffering. And, sometimes, when those traditional teachings don’t seem to work anymore, we may develop a “suspicion” that we are missing something, or that something is being (purposely?) left out.

When it comes to the role of women, the Bible clearly views women as subordinate to men, and so the question becomes: is this God’s absolute truth, to be accepted regardless of the consequences, or is it a reflection of the human-created culture of the time, and not only not to be accepted, but to be challenged.

Throughout history the great majority of cultures have structured society in a patriarchal hierarchy in which women are of less value than men. The biblical world was no different. When it came to inheritance, marriage and divorce, leadership in the temple and synagogue and many other areas of life, women were treated as “second-class” citizens.

If you accept this structure of society at face value and as “truth,” and begin “from above” with that tradition, you will likely be less sympathetic to the struggle of women for equal rights and try to keep women “in their place” because that is the “tradition” of the church.

On the other hand, if your method begins “from below” with the oppression of women and the ways in which they are not treated equally, one will be quicker to criticize and perhaps even abandon certain traditional teachings of the church that maintain such oppression. During my years in seminary and ministry, a tremendous amount of research was being done trying to understand how Jesus, for example, understood the role of women. The conclusion of many scholars was that Jesus did live within the cultural structure of the day in general, but he pushed hard and challenged many of the negative ways in which women were being treated, inviting them to be a significant part of the movement he founded.

Here is an example of how beginning theology from below in experience changed the life of so many women in my generation. A woman grows up in the North American church. She finds much in the teachings of her church that is helpful to her. But perhaps she also experiences a certain amount of oppression of herself as a person. Why is she so often excluded grammatically from the scriptures, as in the passage that states that Jesus, when he is “lifted up from the earth, will draw all men” to himself? [John 12:32 RSV] She hears a lot about Abraham as the father of a great nation. But what about Sarah? Wasn’t she the mother of a great nation? Or did patriarchal church historians interpret her role as lesser? Why has the church taught that as a woman, she is inferior to men, her role in the church is less important and her ideas are less valuable.

This is where “suspicion” may enter. She may realize she does not know this for sure, but she wonders if the subordination and inferiority of women might not be an absolute divine principle, but rather the entrance into theology of patriarchal cultural norms. Now her subordination may no longer be viewed as God’s will, but, in fact, the opposite of God’s will. It is idolatry (treating a human view as God’s will), and, therefore, as something that needs to be combatted. She commits herself to working against female subordination in the church and in theology, and for the liberation of women from patriarchal theological inequality.

Slowly, but surely, I learned of the experiences of women in our culture and church, and the ways in which we both viewed and treated women as unequal. Also, slowly but surely, I tried to become a feminist, while continually aware of how ingrained biases can be and how they thereby unconsciously affect our perceptions and actions.

When I began seminary, in my Master of Divinity (MDiv) class of nearly 100 students only 7 were women. Today more than half of seminarians are women, and of the 68 bishops in the ELCA, almost half are women. What changed theologically that led to this massive ecclesiastical change?

Let me back up for a moment. I was not raised as a feminist. I grew up with very traditional midwestern, white, rural male and female roles. I was pretty much in the dark about women’s issues and roles, and that continued through college. However, I was quickly “liberated” in seminary. The ELCA first ordained women in the predecessor bodies of the ELCA in 1970. When I began seminary two years later, the women in my class were quick to point out sexist language, outdated perceptions of women’s roles in church and society, the patriarchal bias of the Bible and the church and the manifold ways in which women were not treated as equals in church or society. At first, I was defensive. Slowly I began to listen. I began to read. I began to discuss. Over time, I grew in my understanding of the issues women face and their vision of how change could finally occur. Their questions became my questions, including wondering why the church waited thousands of years to ordain women? And why do many present churches continue to refuse to accept women in leadership roles?

Eventually I realized how much church and society had lost by treating women of lesser value and importance. And this became even clearer as the amazing scholarship of women theologians began to appear. However, before encountering those works of theology, it was the storytelling of women that gave me my first insights into the evolution of feminist theology.

As a young pastor in Grand Forks, ND from 1989-1991, I started a pastor book discussion, and our first volume was by Harvard Divinity School’s Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza: In Memory of Her: A Feminist Theological Reconstruction of Christian Origins, “in which she seeks to reclaim early Christian history as women’s history and to reveal biblical traditions as the history of both women and men. These goals help her to answer questions regarding women’s activity in the early Christian movement and to restore the memory of early Christian women’s sufferings, struggles and power to contemporary readers.” [E notes]

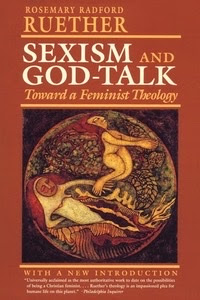

Another powerful book at this time was Sexism and God-Talk by Rosemary Radford Ruether. Phyllis Trible, Professor of Old Testament at Union Theological Seminary in New York, summarizes Ruether’s approach:

Affirming human experience as the basis of all theology, Ruether claims that historically such experience has been identified with and defined by men. The uniqueness of feminist theology is its use of women's experience to expose the male-centered bias of classical theology and articulate a faith that incorporates full humanity. Whereas the traditional paradigm begets domination and subordination, feminism seeks a mutuality that allows for variety and particularity in women and men. The goal is not to diminish males but to affirm both sexes whole, along with all races and social groups.

Feminist theology not only changed my theology in significant ways, it also greatly enriched my life in the church. In my nine callings to parish ministry, only one had had a female pastor before I arrived. However, in my last four calls, I worked on staff with six female pastors. From each of them I learned so much about both theology and ministry, and I experienced countless joys as we all worked together to create a wholistic ministry dedicated to inclusivity, equality and welcome to all people!