Growing up, I developed prejudiced attitudes and racist ideas without myself or my family or my community really being aware of it. You would think that would be hard to do in a little, rural town of 700 in the middle of North Dakota, where the winds blow strong and the snow gets deep.

I don't think this was intentional, at least not consciously. In fact, my dad was a high school history teacher, and I would love to know how he would see the issues of today, but he died in 1965. However, as children, much of our learning about sensitive issues, like sex and race and religion, is picked up by a kind of unspoken osmosis.

First it was the Indians, as we called them. They lived on a reservation 26 miles away. I played basketball on the reservation in grade school, and noticed the unbelievable poverty. Somehow, I picked up the idea that the poverty was because Indians drink a lot and are very lazy. I already knew they were violent, because I had seen John Wayne fight them off so white folks could tame the wilderness of the west, and make something of it.

Then there were the Catholics. They might have been Christian (I wasn’t sure) but they didn’t get to confess their sins to Jesus, like we Lutherans did. They had to go to a priest and spill their mistakes to him, whereas we could keep our sins to ourselves, tell Jesus, and hope our parents didn’t find out. They also thought Mary was God. Could you believe that?

There weren’t any blacks in our town, and hardly any in the whole state. They had been slaves once, which was not a good thing, but things were all better now because we northerners had saved them in what they called the Civil War. And, if they were still treated badly in the South, they could always move to the North where we would surely welcome them.

When we traveled east toward Grand Forks and Fargo, where they raised a lot of sugar beets, I saw Mexicans bending over hoeing the fields. It looked like hard work to me, but they were glad to do it because we treated them much better than where they came from. But they better not try to stay once the farmwork was over.

Now, it is tempting to think these are the impressions of a small child that will be shed as we grow older. But are they? And to what extent?

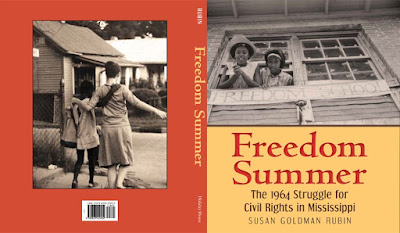

I’m not sure when my thinking began to change, but I can point to some of the main factors. After Dad died, I--who was not known as much of a reader (I just wanted to play sports) --started going to the school library in search of some kind of meaning for my universe that had now fallen apart. In the year after Dad died, I read 47 books not required for school. These included To Kill a Mockingbird, Freedom Summer, and Black Like Me. This was the first time I encountered prejudice and a lack of civil rights, but these books were set in the South, and in no way did I see myself in the stories.

Then, through Luther League, our church’s youth organization, I got to go to some conventions where there was a focus on civil rights, especially after 1968--the year I graduated from high school--which was the year of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., which led to months of protests and riots.

As soon as I hit college, I talked my way into an upper level religion course titled “Seminar on Race Relations,” in which we read James Baldwin’s Go Tell It on the Mountain, Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Stride toward Freedom, Claude Brown’s Manchild in the Promised Land, and Charles Silberman’s Crisis in Black and White. And everything began to change.

I began seminary on the south side of Chicago, in what we used to call the “inner city.” It was almost all black, and the poverty was rampant. Almost all the workers in the stores were black, and over time I got to know many of them. This was my first opportunity to actually have relationships with blacks.

While in my first call in West Fargo, N.D., the American Lutheran Church started offering a seminar on racism. There I learned distinctions among prejudice, racist and racism, that have informed me to this day. Prejudice is “a preconceived opinion that is not based on reason or actual experience.” Racist is “a strong prejudice against people of other races, believing that a particular race is superior to another.” And Racism is “prejudice combined with social and institutional power that creates a system of advantage based on skin color.”

The reason these distinctions are so important is that I have some control over whether or not I am prejudiced or racist, but I have no control over whether I am part of a system of racism. And battling each and all of these things is extremely difficult.

Ever since reading those books as a sophomore in high school I have tried to understand the ways in which I am prejudiced but, because those attitudes were formed mainly unconsciously when I was young, it is much more difficult to redeem them than one might think. In addition to those based on race, I have had to also try to overcome the prejudiced views I grew up with towards women, the mentally ill, gays and lesbians, other religions, other cultures etc. The list goes on and on, and only gets longer with time as we try to stay open to truth and sensitive towards what others are trying to teach us.

Then there still remains racism, which whites have even more trouble dealing with than prejudice. In part this is because it goes to the root ideals of our culture, that we are “individuals” who are to “make it on our own” by “pulling ourselves up by our bootstraps.” It is very difficult for us whites to acknowledge that our society is set up to give us certain advantages that others don’t have.

I went to another anti-racism workshop 15 years ago in Milwaukee. Our group was very mixed racially, and through a number of exercises and discussions, we became quite close to each other. Towards the end of the workshop we were all taken outside, and asked to stand side by side in a line on a large field, holding hands. It felt so good.

And then the leader began to ask us a series of questions: If you were raised in a family with 2 parents, take a step forward. If you grew up with lots of books in your home, take a step forward. If you were ever hungry with no food to eat, take a step backwards. If the police have ever stopped you or someone in your family because of your race, take 2 steps backward. If you needed to go to the doctor, but your family had no insurance or enough money, take 2 steps backwards. If your parents were home to help you with your homework, take 2 steps forward. If you have ever had a slur spoken to you because of your race, take a step backwards. If you have ever gone in a store and a clerk followed you wherever you went, take a step backwards. If your family had enough money for you to go to college, take 2 steps forward.

This exercise was extremely emotional. I began it holding the hand of a black man I had really gotten to like. We tried to hold hands as long as we could, but eventually we had to let go as I moved forward. When the exercise ended, we were asked to look around at the field. People were scattered throughout, but almost everyone in the front was white, and almost everyone way in the back was a person of color. All we could do was stand there silently, and weep.

Many people believe we could be at a watershed moment in the life of our nation. But that will only be if we each have the courage to look at our prejudices and the structure of racism that undergirds our nation. Right now, I am reading Tears We Cannot Stop: A Sermon to White America, by Baptist pastor Michael Eric Dyson, which takes us deep into the experience of being black in America today, and White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk about Racism, by Robin Diangelo.

Many people believe we could be at a watershed moment in the life of our nation. But that will only be if we each have the courage to look at our prejudices and the structure of racism that undergirds our nation. Right now, I am reading Tears We Cannot Stop: A Sermon to White America, by Baptist pastor Michael Eric Dyson, which takes us deep into the experience of being black in America today, and White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk about Racism, by Robin Diangelo.

Both will knock you to your knees. But that is the only way we have a chance to rise up. “Jesus answered them, ‘Very truly, I tell you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains just a single grain; but if it dies, it bears much fruit.’” [John 12:24]

thank you Pastor Brian.

ReplyDelete