How My Theology Has Changed, Thank God

Part I: Don’t Throw God Out with the Bath Water

One of the strange things about humans is that we get so attached to our beliefs and theology (how we understand God and the world) that we often throw out God before we throw out, or revise, our theology. This is what I tried to do in my college years, but, thank God, rather than throwing out God I continued the intellectual and emotional struggle to deepen and enlarge my theology to better reflect the way the world is and what I actually do believe, rather than what I felt like I was “supposed” to believe.

|

The spiritual journey is a dangerous quest. It is a quest, which the dictionary defines as “a long or arduous search for something,” [Oxford] and the holy grail is always truth: truth about the world, about me, about God, about how God wants us to relate to one another and all creatures, big and small.

It is dangerous because to be true to this quest, we will have to be honest about and with ourselves. We begin the quest with all kinds of baggage, and some of it will need to be cast off and replaced, hopefully with something better and “more authentic, more true.” I know my theology, which has evolved through so many iterations already, will no doubt need to continue to evolve, which again, according to the dictionary, means “the gradual development of something, especially from a simple to a more complex form.” [Oxford]

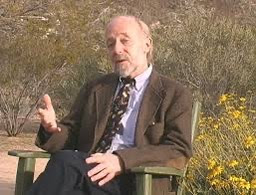

As I describe the evolution of my spiritual journey, my traveling partner will be the late Dr. Marcus Borg (1942-2015). I choose him because, not only is he one of the most profound New Testament biblical scholars and theologians of the past half century, but because his Lutheran upbringing was so similar to mine, and his writings have helped me understand how I was raised and what I was taught--from the very beginning--to believe about God and the world.

Marcus grew up in rural North Dakota, just as I did, eight years before me. He attended Concordia College in Moorhead, Minnesota, just as I did, and he returned there, with his doctorate, to teach right before I arrived, and right after I left. (I assume this was a coincidence.)

I first encountered his work thirty years ago when I was a pastor in Fargo, ND, and I read (and then taught in the congregation) his 1994 book, Meeting Jesus Again for the First Time, in which he describes the elements of the Christian theology in which he was raised, essentially the same theology in which I was raised 100 miles to the west of him.

|

| My Home Church, North Viking Lutheran, Maddock, ND |

I will describe that theology, which I label Lutheran Prairie Pietism--with its pros and cons--in the next two blog posts. But, before getting to that, it is helpful to consider Borg’s description of the three-step theological process that informed his own life. This is the move from precritical naivete through critical thinking toward postcritical affirmation or conviction. (This sequence was first developed by French philosopher, Paul Ricoeur)

In the first stage of precritical naivete, we take it for granted that whatever significant authority figures tell us is true is indeed true. And we have no reason to think otherwise (Borg, Convictions, 53-54). Along with the cultural beliefs that a tooth fairy puts money under our pillow and Santa Claus brings gifts through a chimney, we were told the world was created in six days, a special star led the Wise Men from the East to Jesus, God is all-powerful and controls all that happens, sitting on a throne watching everything we do and think, and men are more important in church and society than women.

The critical thinking stage begins when you start to develop a “suspicion” (this term is from Liberation Theology, which we will discuss later) that something you have been taught may not be “actually” true. A common example of this is the study of science. Christians and the church struggled with Copernicus’ assertion that the earth is not “actually” the center of the universe, as the Bible implied. I can still remember learning in high school about the age of the stars and universe, and wondering how this could be when the Bible had all of creation happening in a week. The common response that for God a day is a thousand years was not particularly helpful.

However, the real challenge comes when you move from intellectual curiosity to emotional pain. Like Marcus Borg, whose father died in Borg’s early twenties, my dad died when I was 15. This was followed by my mom’s death when I was 17. For a while my Lutheran pietism kept me going. But then a crack in my faith began to form. After all, if God did indeed control everything that happened in the universe, then why would God “choose” to take both my parents from me at such an early age? I was, in fact, facing in my late teens the issue all religious humans face sooner or later: what is the relationship of God to human suffering and pain?

This was the point when I was first tempted to throw the baby (God) out with the bath water (my childhood, precritical, naïve theology). The only way I could keep from doing that was to use critical thinking to build a new theological and spiritual understanding in the journey for a postcritical, authentic, integrated theology representing my deepest-held affirmations and convictions which was, at the same time, more in harmony with what we know about the world.

In the next post we will consider, first, the strengths of Lutheran Prairie Pietism when it came to the issue of loss, grief and God’s Will, and then, in the third post, the ways in which my childhood theology no longer worked for me, and which aspects of it I had to jettison.

Following that I will share the insights I have gleaned from so many differing people and places as I began to develop my own postcritical theology, which includes majoring in college in both Philosophy and World Religions, and then, later, the study of the Theology of Hope, the Crucified God, Process Theology, Liberation Theology, the Historical Jesus, Eastern Mysticism, the Beloved Community articulated by Martin Luther King, Jr., and, finally, Revolutionary Love (Valarie Kaur), which includes a commitment to and hope for the future of those whom I love and the world of strangers out there who are a part of me I don’t yet know. (Kaur)

Sitting on the edge of my seat for the next one….

ReplyDelete