How My Theology Has Changed, Thank God

Part X: Latin American Liberation Theology

|

My first eight posts in this series articulate the theological ways I searched to find meaning again, and a positive relationship with God, in response to the grief that consumed much of my life after the deaths of my parents when I was in high school, and my first wife, Pauline, after ten years of marriage.

In my last post, on Feminist Theology, I described another way in which our theology can change. It is not in response to our own painful experience, but to the painful experiences of others that is shared with us when we have an open mind and heart. The remainder of my posts in this series will be of this type, and most of them fall into the category of what we call “liberation” theologies,” which search to free us from old ways that no longer work, if they ever did.

Traditional theology, which we often call Orthodoxy, begins “above” with traditional interpretations of theology and with the teachings of the church and then applies those understandings to our life in the world. Liberation theologies always begin “below,” in our lived experiences, or as we learn of the lived experiences of others and then turn to the tradition for insight and guidance.

One of the primary ways in which this happened for me was on my first trip to the interior of Mexico in December 1983. The travel seminar began in Mexico City where two Catholic Sisters took us to a massive landfill on the outskirts of the city, the fourth largest city in the world with a population over 23 million people. Our van stopped at the top of the dump ground so we could get out and look down into the landfill. It was massive, with garbage piled high and deep as far as you could see, and an odor so strong it made your eyes water.

|

| Photo taken by me, December 1983 |

We drove down into the landfill where we found families living in lean-to homes, made from whatever materials they might find, and making their living by sorting through the garbage, for food to eat and for items they might sell. And right in the middle of this massive landfill was a soccer field for the kids to play on. We also saw large garbage bags that were turquoise in color. When we asked the Sisters why they were that color, they told us it was because that was how they got rid of hospital garbage, and the turquoise color was so that people would know not to go through it.

However, driving a little further, we saw children going through the turquoise bags. We could not believe what we were witnessing! It was impossible to hold back the tears. The Sisters then explained that the poverty is so great that there is a waiting list of people who hope to live in the landfill one day. A child may be born in the landfill, grow up there and have children of their own, and then die there. It may be the only life some people ever know.

In the months to follow, that painful and bewildering experience haunted my dreams and my theological reflection. How can someone see, smell and feel such a painful reality and not respond in some way? Two years later, when we had moved to Cuernavaca, Mexico to live and teach, I began to find an answer.

Dr. Mark W. Thomsen was the Director of the Division for World Mission, and he had an idea for a theological conference at our Lutheran seminary in Mexico City, which was scheduled for December of 1985. The American Lutheran Church invited 14 South American theologians and 14 North American theologians to gather to discuss the meaning of Lutheran theology for the contemporary era, especially as it pertained to the massive poverty throughout the southern hemisphere. The plan was to take 14 themes of Lutheran theology, with 7 major presentations made by Southern and 7 by Northern theologians, with another theologian from the opposite hemisphere responding to each lecture.

Invitations were sent to 28 Lutheran theologians, 14 From North America and 14 from Central and South America. Every single one accepted the invitation, anxious to begin what we all knew would be a profound dialogue.

|

| Dr. Milton Schwantes |

I remember vividly the beginning of the conference. It felt like being at the United Nations. Everyone had headsets, as all presentations and discussions would be translated into Spanish, Portuguese and English. As the conference was about to begin, a profound theologian from Brazil, Dr. Milton Schwantes, asked to speak. First, he thanked the planners for the invitation to come and he stated how pleased he and the other southern theologians were to be part of such a dialogue. Then he went on to say, “However, we have a problem with how this conference is set up. You are starting with doctrines of Lutheranism, and we are asking what these teachings mean for us today. However, that is not the way we do theology in the South. We begin with the pain and suffering of our people, and then ask what our theology and the church has to say to them.”

For a few moments, the conference fell into stunned silence. With those few words Dr. Schwantes had captured the challenge before us. He was advocating for “theology from below,” the beginning of all liberation theologies. This was the answer to my intuition that the spiritual journey does not begin with doctrine, but with our quest to find meaning and hope in the midst of the suffering we ourselves experience, and the suffering we encounter all around us in the world.

It was time for me to think through again the meaning of “salvation,” which, for me, growing up in the church, was our primary goal and included two elements: living in the forgiveness of sins in this life, and the hoped-for entrance into a life after death in the presence of God. However, that was not the primary understanding in the biblical world. The Greek soteria meant "deliverance from powers of harm, which included rescue from serious peril, being saved from sin through forgiveness, and experiencing health and well-being. [See Shirley Paulson, The Bible and Beyond Blog]

Focusing on the teachings of Jesus, one can readily see this understanding: he focused on freeing people from illness, racism, poverty, loneliness, and then invites his followers into a Movement built on equality, mercy, compassion, reconciliation, love and hope in the midst of the many calamities of life. For liberation theology, this means calling the church to include in its understanding of salvation the freeing of persons from the many ways in which they are oppressed, abused, marginalized and discounted in the earthly realm. As such, this approach searches for a true and whole freedom not only from spiritual sin, but from the many ways people are imprisoned by the conditions in their lives.

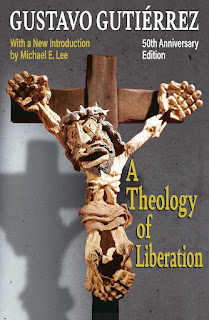

Last October Gustavo Gutiérrez of Peru, called the “father of liberation theology,” died at age 96. In 1971 he had published A Theology of Liberation: History, Politics, and Salvation, which grew out of his concern for people experiencing economic poverty amid the collapse of political projects in the 1960s that tried to modernize the region, exacerbated by the political repression by military juntas in several South and Central American countries. The result was widespread violence and poverty—something that, for Gutiérrez and his colleagues, was not natural, but produced by severe social and economic inequality.

Leonardo Boff, a Brazilian theologian, explains his understanding of this new theology: “That was the innovation introduced by Gustavo Gutiérrez and others—including myself—when we conceived theology starting from the suffering and oppression faced by the great majority of the Latin American people. The poor are oppressed, and all oppression cries for liberation,” [See Eduardo Campos Lima, The Christian Century, November 1, 2024.]

Liberation theology proposes to fight poverty by addressing its alleged source, the sin of greed. In so doing, it explores the relationship between Christian theology (especially Roman Catholic) and political activism, especially in relation to economic justice, poverty, and human rights. The principal methodological innovation is seeing theology from the perspective of the poor and the oppressed. For example, Jon Sobrino, of El Salvador, argues that the poor are a privileged channel of God's grace. According to Gutiérrez, God is revealed as the One with deep concern for those people who are "insignificant", "marginalized", "unimportant", "needy", "despised", and "defenseless". Moreover, he makes clear that the terminology of "the poor" in the Christian Bible has social and economic connotations that etymologically go back to the Greek word ptōchos, explaining: "Preference implies the universality of God's love, which excludes no one. It is only within the framework of this universality that we can understand the preference, that is, 'what comes first'." [Gutierrez,The God of Life, p. 112.]

I was blessed living in Mexico to see liberation theology at work in the lives of the poor. I attended many Bible studies, called Base Christian Communities, where folks in poor neighborhoods gather to explore the relationship of God and the Bible to their poverty. I marveled at people’s generosity with each other, in spite of their great poverty, and their commitment to support each other and then work together to confront the ways both church and government often ignored them and even at times took advantage of them.

These powerful experiences became the basis of my Doctor of Ministry thesis on Liberation Theology and the Base Christian Community Movement, and this new theological orientation would eventually change not only how I understood the world but also the ways in which I would do ministry. From preaching to confirmation to adult education I tried to begin with the pain and suffering and joys of the people with whom I worked as together we searched our rich and powerful Biblical and theological traditions for insight, guidance and inspiration. [For further study, see my recent book available from Amazon: Freed to Love and Live Again: My Journey through Grief to Wounded Healing, a Liberating Theology and Social Justice Ministry, especially Chapters 3-4.]

St. Paul talks about the power of faith, hope and love, and I saw in these Base Communities all three, including an unrelenting hope stronger than suffering and even death. As Rubem Alves of Brazil wrote in his book, Tomorrow’s Child:

What is hope?

It is the pre-sentiment that imagination

is more real and reality is less real than it looks.

It is the hunch that the overwhelming brutality

of facts that oppress and repress us

is not the last word.

It is the suspicion that reality is more complex

than the realists want us to believe.

That the frontiers of the possible are not

determined by the limits of the actual;

and in a miraculous and unexplained way

life is opening up creative events

which will open the way to freedom and resurrection –

but the two – suffering and hope

must live from each other.

Suffering without hope produces resentment and despair.

But, hope without suffering creates illusions, naïveté

and drunkenness.

So let us plant dates

even though we who plant them will never eat them.

We must live by the love of what we will never see.

That is the secret discipline.

It is the refusal to let our creative act

be dissolved away by our need for immediate sense experience

and is a struggled commitment to the future of our grandchildren.

Such disciplined hope is what has given prophets, revolutionaries and saints,

the courage to die for the future they envisage.

They make their own bodies the seed of their highest hopes.

This hope grows out of an unrelenting focus on the love of God for the whole world and a trust not only in God, but in the community of love that surrounds each of us. This deep spiritual understanding is expressed powerfully in the poetry of Julia Esquivel of Guatemala, who was an elementary school teacher who also studied theology:

Mary Erickson, Guatemala, 1986

—From Threatened with Resurrection

Picture of Christ Figure: Hunger cloth from the Misereor humanitarian aid community in Wernberg Monastery, Villach Land district, Carinthia, Austria, EU. Via Wikimedia Commons

No comments:

Post a Comment